Computer Architecture Simulation & Visualisation

Return to

Computer Architecture Simulation Models

MU5

MU5 was the fifth computer system to be designed and built at the

University of Manchester, in succession to a series of innovative

projects dating back to the late 1940s. MU5 introduced a number of new

ideas, particularly in terms of its instruction set, which was

designed with high-level language compilation in mind, and novel uses

for associative stores. The technical aspects of the project have been

well documented in numerous papers and a book. Many of the design

ideas developed in MU5 were used in the ICL 2900 series of computers.

This webpage describes the design of the MU5 computer, explains how

the HASE simulation model works and includes a list of relevant

publications. The most recent version of the model (V4.1) includes a

GLOBALS parameter Program that can be edited after the model has

been loaded into HASE. Program can take values of 1, 2 or 3,

allowing the user to select one of three programs contained in the

model. After editing, clicking the "Write Parameters" button

updates the model's parameters file.

Program 1 demonstrates the operation of the MU5 Name Store,

Program 2 executes a scalar product program, Program 3 demonstrates

the use of string processing instructions.

updates the model's parameters file.

Program 1 demonstrates the operation of the MU5 Name Store,

Program 2 executes a scalar product program, Program 3 demonstrates

the use of string processing instructions.

The files for version 4 can be downloaded

from MU5_V4.1.zip.

Instructions on how to use HASE models can be found at

Downloading, Installing and Using HASE.

Overview

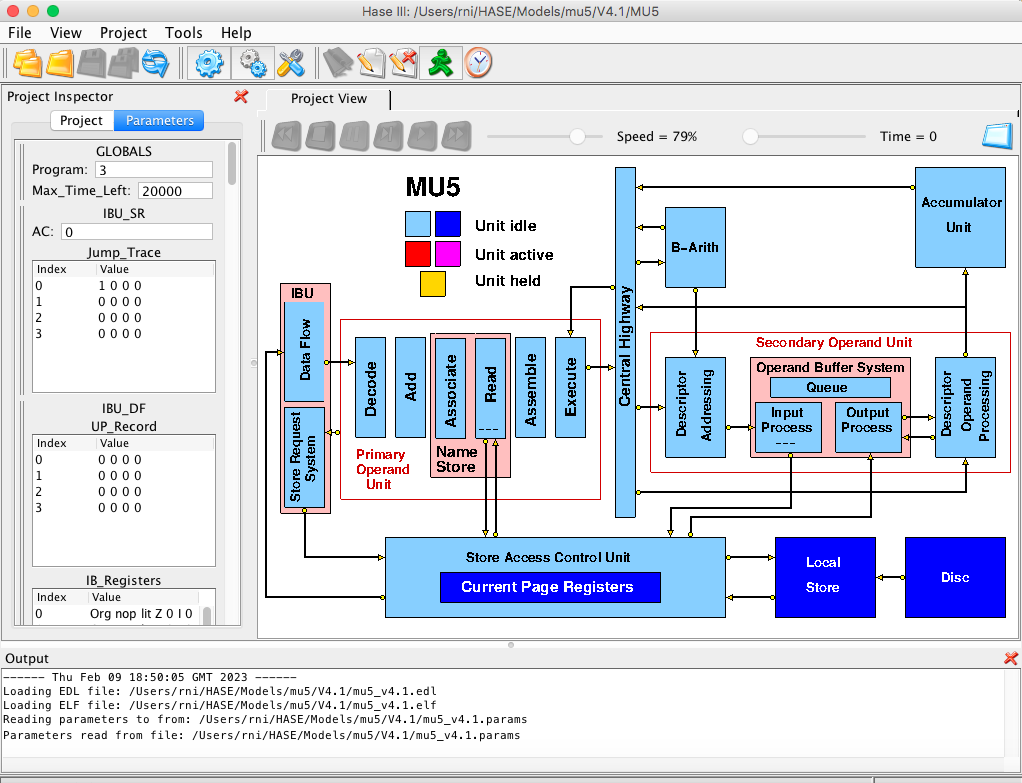

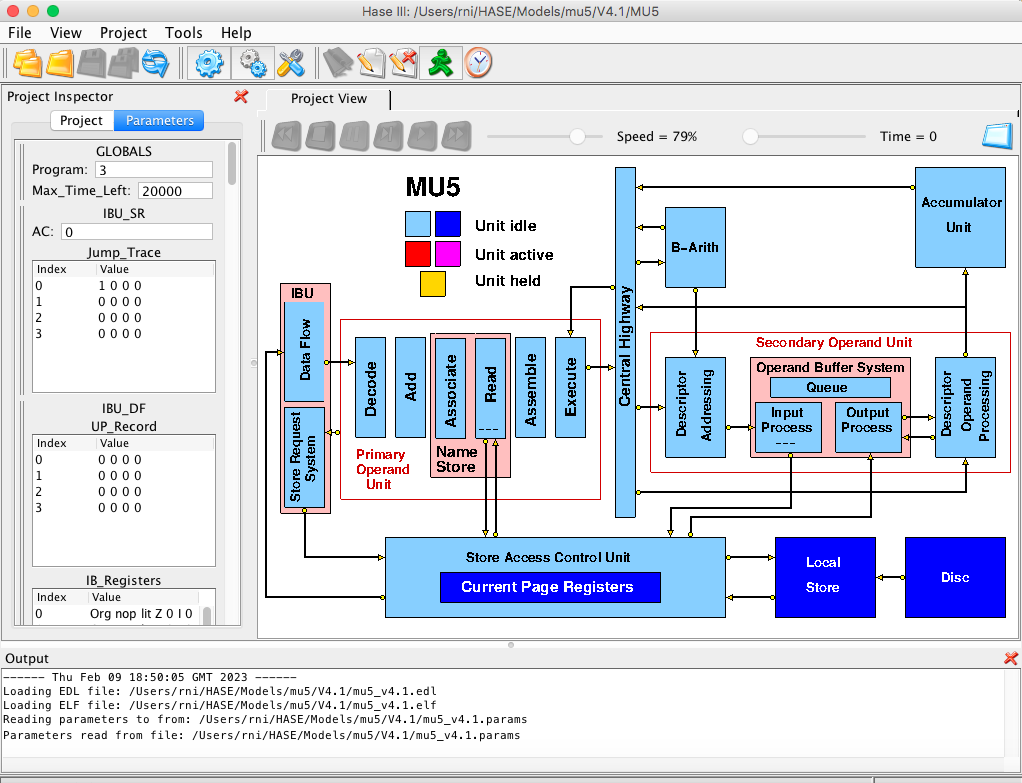

Figure 1 shows an image of the HASE user interface with the

simulation model of MU5 in the main (right hand) Project View pane and

model parameters (e.g. register and store contents) in the

(left hand) Project Inspector pane. The lower, Output pane shows

information produced by HASE. The icons in the top row allow the user

to load a model, compile it, run the simulation code thus created and

to load the trace file produced by running a simulation back into the

model for animation.

Figure 1. The MU5 simulation model loaded into HASE

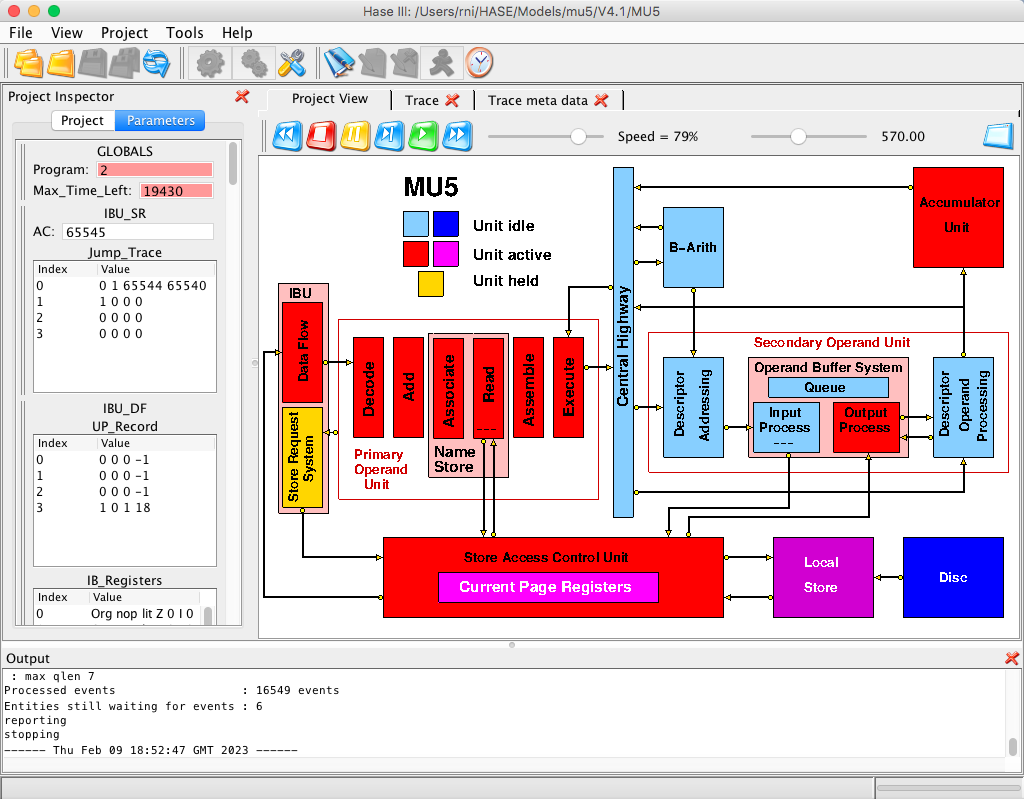

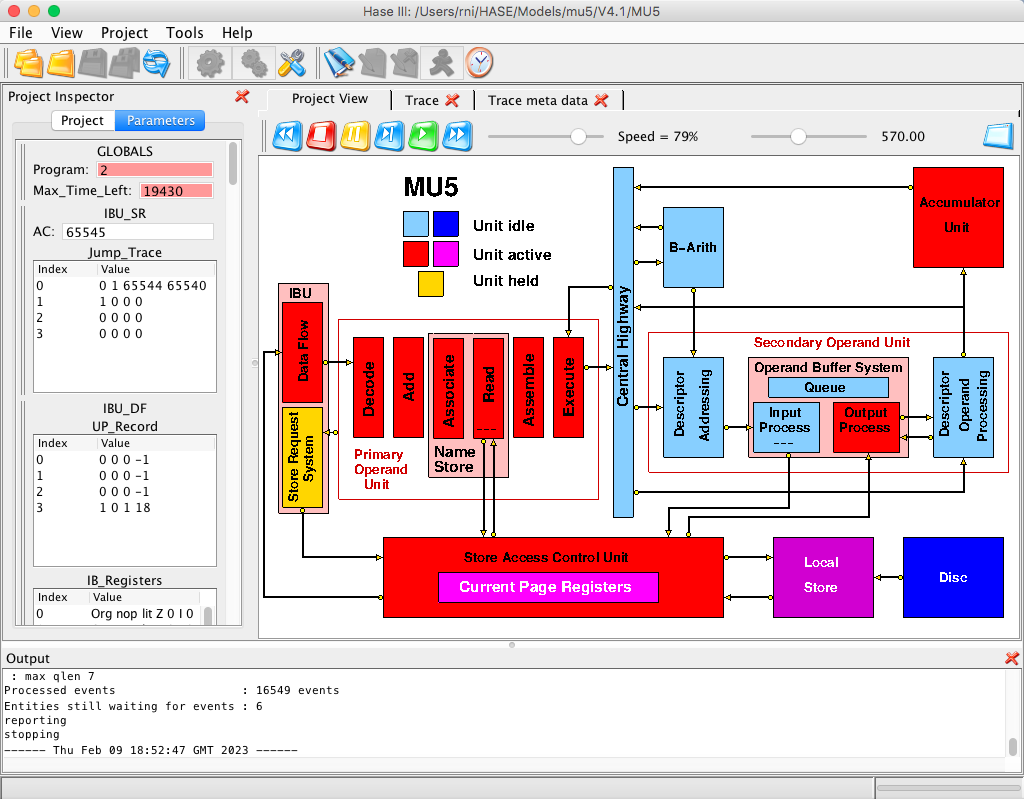

Once a trace file has been loaded, the animation control icons at the

top of the Project View window become active (Figure 2). From left to

right, these allow the animation to be rewound, stopped, paused,

single stepped, run or fast forwarded to the end. As the animation

proceeds, packets of information can be seen passing between entities

while the entities themselves change colour to reflect their states

(idle, busy, waiting).

Figure 2. The MU5 simulation model during animation

The model contains 23 active units (entities in simulation terms).

These are the Console, the two parts of the Instruction Buffer Unit,

the six stages of the Primary Operand Unit (PROP), plus one for PROP

itself (containing the beat generation code), the Central Highway, the

B-Arithmetic Unit, the Descriptor Addressing and the Descriptor

Operand Processing Units, the three sections of the Operand Buffer

System, the Accumulator Unit, the Store Access Control Unit

(containing the Current Page Registers), the Local Store and the Disc

Store. Although they are shown on-screen as parts of the model, the

IBU, Name Store, SEOP and Operand Buffer System entities are simply

icons, with no corresponding simulation code. The 23rd entity is a

time counter containing a limit on the total number of simulation time

steps, to prevent run-aways; its icon is the key to the unit

states.

MU5 Design Considerations

During the design of MU5 the prime target was fast, efficient

processing of high-level language programs in an interactive

environment. This requirement led to the need for an instruction set

which satisfied the following conditions:

- Generation of efficient code by compilers must be easy.

- Programs must be compact.

- The instruction set must allow a pipeline organisation of the

processor leading to a fast execution rate.

- Information on the nature of operands should be available to

allow optimal buffering of operands.

Algol and FORTRAN were taken as being typical of two major classes of

programming languages in common use at the time, distinguished by the

use of recursive routines (or procedures) and dynamic storage

allocation in the former, and non-recursive routines and compile time

storage allocation in the latter, but having the following features in

common:

- Each routine has local working space consisting of named variables of

integer (fixed-point) and real (floating-point) types, and structured

data sets (arrays, for example) which are also named.

- A routine may refer to non-local names either of an enclosing routine

or in a workspace common to all routines.

- Statements involve an arbitrary number of operands which may be real

names, array elements, function calls or constants.

In order to reconcile feature 3 with condition 1 and 4, it was decided

that there would be an address form corresponding to each of the

different operand forms. However, it was felt that to have more than

one such operand specification per instructions would conflict with

conditions (2) and (3). The option of using addressable fast registers

to allow short instructions was also rejected. There were two

arguments against registers. The first was the desire to simplify the

software by eliminating the need for compilers to optimise their use.

The second was the desire to avoid the need to dump and restore

register values during procedure entry and exit and process changes.

The alternative arrangement proposed for MU5 was a small associatively

addressed Name Store, described in more detail below.

The MU5 instruction set

To avoid tortuous grammatical constructs, the following description

of MU5 is written in the present tense, even though the real MU5 no

longer exists.

The instruction format chosen for MU5 represents a merger

of single address and stacking machine concepts. All the arithmetic

and logical operations involve the use of an accumulator and an

operand specified in the instruction, but there is a variant of the

load order (*=) which causes the accumulator to be stacked before

being re-loaded. In addition, there is an address form (STACK) which

unstacks the last stacked quantity. Thus the expression

RESULT := (A + B) * ((C + D)/(E + F))

can be compiled into

| ACC = A |

| ACC + B |

| ACC *= C |

| ACC + D |

| ACC *= E |

| ACC + F |

| ACC ∅ STACK |

| ACC * STACK |

| ACC => RESULT |

The function ∅ is reverse divide

(i.e. ACC = STACK/ACC); if the operand to the left of

an operator is stacked, it subsequently appears as the right hand side

of a machine function (as the dividend in this case). Thus, for the

non-commutative operations - and /, the

corresponding reverse operations have to be provided. In pure stacking

machines, all subtractions and divisions are implicitly reverse

operations.

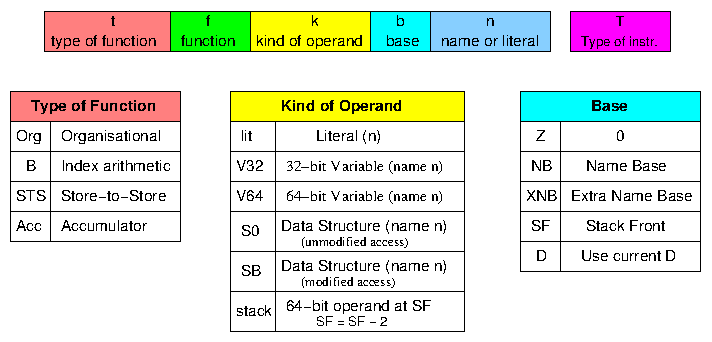

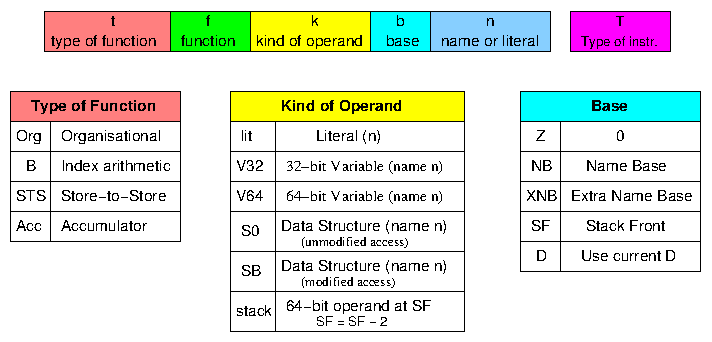

The instruction set is summarised in Figure 3. There are two basic

formats, one for computational functions and one for organisational

functions (control transfers, base register manipulations, etc.).

They are distinguished by the

type of function bits and use four and six bits respectively

to specify the function. The remaining nine or seven bits specify

the primary operand. The

k field indicates the kind of operand, and determines how

the n field is interpreted. Where the k field

indicates the Extended Operand Specification, the instruction is

extended by an additional 16 bits in the case of a name, or by 16, 32,

or 64 bits in the case of a literal.

Figure 3. The MU5 instruction set

The virtual address space is formally segmented: the unique identity

of store words belonging to different processes is maintained by

splitting the address into three separate fields, a 4-bit Process

Number, a 14-bit Segment Number, and a 16-bit address defining a

32-bit word within a segment. Segments 8192 to 16383 are common to all

processes, allowing a single copy of a compiler, for example, to be

shared by all active processes. Scalar variables are normally held in

a single segment of a process (normally segment 0) at addresses formed

by adding the 6 or 16-bit name in the instruction to the contents of

the Name Base register (RNB). The name segment number and the process

number (both held in special registers in the processor) are

concatenated with these addresses to form the full virtual addresses

required for store accessing. The value held in RNB is unique to the

name space associated with each procedure, and is altered at each

procedure change. Accesses to names of other procedures and to common

variables are made using the Extra Name Base (RXNB), while using zero

as base allows absolute addressing into the Name Segment (to access

the Name Base values of different procedures, for example). The Stack

Front register (RSF) points to the area immediately beyond the name

space of the current procedure, so that stacked variables are

contained within the same address space as the names. RSF is

automatically incremented or decremented during the execution of a

stacking function or a STACK operand access respectively.

Scalar variables can be of size 32 bits and 64 bits. They are accessed

from a 32-line Name Store using an address formed by adding the name

to the base register specified in the instruction (implicitly the Name

Base in 16-bit instructions). The Name Store has two parts, 32

associatively accessed address registers and 32 64-bit value

registers, so although a name + base address can point to a 32-bit

variable, the base registers themselves can only point to 64-bit

quantities. Thus the least significant bit of each of the base

registers is set to zero and the name of a 64-bit variable is shifted

left one place before being used to form an address.

Access to array elements is achieved through a descriptor mechanism.

When a data structure element is specified by the k field, the

corresponding primary operand is a 64-bit descriptor. This descriptor

is sent to a D-unit within the processor, together with the contents

of the B register if the k field specifies modification. The

D-unit interprets the descriptor and makes a secondary store

access for the element. This detachment of secondary addresses from

instructions, and the use of names within instructions, allows the

full 30-bit virtual address space available to a process to be

referenced by 16-bit instructions.

There are two main types of descriptor:

| String descriptor: | Ts | Length | Origin |

| Vector descriptor: | Tv | Bound | Origin |

| | 8 | 24 | 32 |

String descriptors describe strings of bytes. The length field

specifies the number of bytes, and the origin specifies the byte

address of the first byte. Strings are normally used in conjunction

with string processing orders (which may be two-address operations

involving the use of two descriptors). These orders provide

facilities for the manipulations of data records in languages such as

COBOL, PL/1 and Algol 68 (move, compare, logically combine, etc.).

The size of the elements in a vector is specified within the type bits

(Tv) and may be between 1 and 64 bits. If the operand access is

modified, the modifier must be greater than or equal to zero and less

than the bound. This check is carried out automatically by hardware

with virtually no time penalty, and removes the need for the costly

software bound check which is often required, particularly during

program development.

The Simulation Model

In any simulation modelling system there is a trade-off between

accuracy and performance. HASE was designed primarily as a high-level

visualisation tool for computer architecture students and therefore

simulates systems at register/word level rather than bit level. This

inevitably imposes some limitations on the way models can be

constructed, e.g. registers are modelled using typed variables and

stores are modelled as arrays of typed variables. Thus the HASE MU5

simulation model is intended to provide a visual demonstration of the

workings of the processor and memory system, rather than being

designed to run real MU5 programs. There are also constraints on

nomenclature. The type field, function field, etc in instructions are

modelled using the C++ enum construct, the elements of which can only

contain alphanumeric characters. Thus the MU5 function

'NB =', for example, is represented in the model as

'NBld' and the base registers are given the names used in the

hardware design diagrams (RNB, RXNB, RSF) to avoid clashes with NB,

XNB, SF in instructions.

The Instruction Set

The MU5 instruction set used in the model follows the spirit of the

original, rather than the detail, in particular because the instruction

format and size have to be fixed in HASE, rather than both being

variable as they were in MU5. In fact these restrictions are not

particularly significant: it was difficult for compilers to optimise

object code to use the short-form 16-bit format, so apart from the

long literals option (32-bit and 64-bit), most instructions were 32

bits long anyway. The instruction set of the ICL 2900 series, which

was closely modelled on that of MU5, did not allow the long literal

options and the MU5 hardware designers would themselves have gladly

forgone this option.

Figure 4 shows the instruction set used in the model..

The additional Type of Instruction (T) character is included in

instruction registers, and in packets containing instructions,

to represent the extra function bits that were used in the

hardware of MU5 to control the execution of instructions. Details

are given below in the Primary Operand Unit section.

Figure 4. The HASE MU5 instruction set

The functions are shown in the table below. Empty boxes correspond to

functions that have not yet been implemented in the model (and in some

cases may never be), or did not exist in the real MU5. "Op" means

"operand"

The B functions correspond exactly to those implemented in MU5. COMP

(compare) sets the two test bits T1 (= 0 / ≠ 0)

and T2 (≥ 0 / < 0) according to the result of B -

operand; B itself remains unaltered. In the real MU5, a third

test bit (T0) was set to 1 if the comparison produced an overflow; in

the model, an arithmetic overflow would be caught by the underlying

runtime system, so T0 is not implemented. CINC

(compare & increment)

acts similarly but increments B after the comparison. CINC was

intended for use with a subsequent conditional branch instruction in

the implementation of for loops.

The ACC (Accumulator) functions are implemented in the model in

exactly the same way as the corresponding B functions, i.e. as

32-bit integer operations, rather than as floating-point

operations. The reason for this is explained below in the Address Space

section.

The STS functions (SLGC, SMVB, SCMP, BLGC, BMVB, BMVE, SMVF, BSCN and

BCMP) perform string processing operations. They were designed for use

in record processing applications written in languages such as COBOL,

PL/1 and Algol68. Their operation is explained in the description of

the actions that take place during execution of the String Processing

Program (Program 3) in the model,

| Organisational |

| Function | Action | Function | Action | Function | Action | Function | Action |

| BR | ->

(CO = CO + Op) | EXIT | | | | | |

| JUMP | CO = Op | RETURN | | | | | |

| XC0 | eXecutive Call

not implemented | XC1 | | XC2 | | XC3 | |

| XC4 | | XC5 | | XC6 | | STACK LINK | |

| MS = | | | | | | SET LINK | |

| XNB_LD | RXNB = Op | | | XNB_PL | RXNB = RXNB + Op | XNB_ST | RXNB => Op |

| SF_LD | RSF = Op | SF_PL | RSF = RSF + Op | SFNB_PL | RSF = RNB + Op | SF_ST | RSF => Op |

| NB_LD | RNB = Op | NBSF_PL | RNB = RSF + Op | NB_PL | RNB = RNB + Op | NB_ST | RNB => Op |

| BReq | -> if = 0 |

BRne | -> if /= 0 |

BRge | -> if >= 0 |

BRlt | -> if < 0 |

| BRle | -> if =< 0 |

BRgr | -> if > 0 |

OVERFLOW | -> if overflow

(not implemented) |

BRBn | -> if Bn = 1 |

| Bneq | Set Bn if = 0 |

Bnne | Set Bn if /= 0 |

Bnge | Set Bn if >= 0 |

Bnlt | Set Bn if < 0 |

| Bnle | Set Bn if =< 0 |

Bngr | Set Bn if > 0 |

OVERFLOW | Set Bn if overflow

(not implemented) |

BnBn | Set Bn if Bn = 1 |

| | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | |

| B | STS/D | ACC |

| Function | Action | Function | Action | Function | Action | Function | Action |

| LD | B = Op | XDO_LD | XDO = Op | DO_LD | DO = Op | LD | ACC = Op |

| LDD | B = Op - 1 | XD_LD | XD = Op | D_LD | D = Op | nop | |

| SLD | Stack B

B = Op | STACK | Stack Op | D_SLD | Stack D

D = Op | SLD | Stack ACC

ACC = Op |

| ST | B => Op | XD_ST | XD => Op | D_ST | D => Op | ST | ACC => Op |

| ADD | B = B + Op | XDB_LD | XDB = Op | DB_LD | DB = Op | ADD | ACC = ACC + Op |

| SUB | B = B - Op | | | | | SUB | ACC = ACC - Op |

| MUL | B = B * Op | | | MOD | DO = DO + Op

DB = DB - Op | MUL | ACC = ACC * Op |

| DIV | DUMMY | XMOD | XDO = XDO + Op

XDB = XDB - Op | | | DIV | ACC = ACC / Op |

| XOR | B = B xor Op | SLGC | | BLGC | | XOR | ACC = ACC xor Op |

| OR | B = B v Op | SMVB | | BMVB | | OR | ACC = ACC v Op |

| SHL | B = B ← Op | | | BMVE | | SHL | ACC = ACC ← Op |

| AND | B = B & Op | | | SMVF | | AND | ACC = ACC & Op |

| RSUB | B = Op - B | | | | | RSUB | ACC = Op - ACC |

| COMP | set T1 & T2 acc.

B - Op | | | BSCN | | COMP | set T1 & T2 acc.

ACC - Op |

| CINC | set T1 & T2 acc.

B - Op; B = B + 1 | SCMP | | BCMP | | nop | |

| RDIV | DUMMY | | | | | RDIV | ACC = Op / B |

The Address Space

Because each memory is modelled as an array of elements of a

particular HASE types, it is not possible to mix instructions,

integers (fixed-point numbers) and reals (floating-point numbers) in

one array. However, in a paged machine it is possible to allocate

separate blocks of memory to different types. This works well in the

HASE Atlas model because the fixed-point and floating-point numbers

and code can be in separate areas of the virtual address space. In

MU5, however, the address space is formally segmented into a segment

for named variables (the Name Segment), segments for code and segments

for array elements. In the Name Segment, fixed-point variables,

floating-point variables and descriptors are intimately mixed

together. Descriptors can be represented fairly simply as a pair of

32-bit variables, but for floating-point variables the choice is

between representing them as the integer equivalents of their

floating-point bit patterns (as in version 2 of the HASE DLX model),

and implementing the appropriate conversions, or simply confining the

model to fixed-point variables. The latter option was chosen for

MU5.

The translation of virtual to real addresses in MU5 used a more

complex paging mechanism than that used in Atlas (the first virtual

memory computer). In the intervening years, main memory sizes had

expanded enormously, requiring the use of many more paging

registers. However, the nature of associative technology made this

infeasible, so in most large computers with virtual memory, only a

subset of the full virtual-to-real mapping table is held in hardware,

as Current Page Registers (CPRs). CPRs differ from PARs in that they

require a Real Address Field as well as an associative Virtual Address

Field. Using CPRs means that on many occasions when a page fault

occurs, the operating system just needs to update a Current Page

Register without the need for any transfer of memory contents between

the main store and the backing store.

MU5 had 32 CPRs, implemented in such a way that the page size could be

varied. For user programs the page size was 256 32-bit words, meaning

that the page table for any one segment (of 65536 words) could itself

be contained in a single page. For system programs, the page size was

equal to the segment size. In the HASE model of MU5, the page size is

256 words and there are just four CPRs. At the start of a simulation

the CPRs all have their Valid bits set to 0, so the first request for

an instruction, integer variable or character causes a page fault. In

the real MU5 a page fault would have caused an interupt and the

operating system would have organised the updating of a CPR and the

transfer, if necessary, of the required page from the Disc or Mass

Store to the Local Store via the Exchange (c.f. [15]). The

model simply includes the Disc Store, containing the three programs

and connected directly to the Local Store. The allocation of CPRs and

blocks in the Local Store is built into the Hase++ code of the CPRs

and Disc Store. The occurence of a page fault is indicated by the

Store Access Control Unit entering its Held state.

The Primary Operand Unit

The design of the Primary Operand Unit in the model follows as closely

as possible the design of the Primary Operand Unit (PROP) in the real

MU5. It consists of six pipeline stages, each modelled as a separate

entity and designated Decode, Add Associate, Read, Assemble and

Execute. The Decode stage receives instructions from the Instruction

Buffer Unit and decodes them to determine the source and/or sink of

the operand(s) and whether the instruction is to be executed by PROP

itself or sent to another unit. The Add stage forms the sum of

name+base for appropriate instructions. The result is presented to the

associatively accessed virtual address field of the Name Store in the

Associate stage and, if the address is present, the value is read from

the value field of the Name Store in the Read stage. (The Name Store

in MU5 contained 32 lines, 28 for user programs and 4 for the

operating system; the Name Store in the model just contains 8 user

lines, making it easier to demonstrate the actions involved in

managing the Name Store.) The Assemble Stage selects the appropriate

parts of this value (e.g. all 64 bits or the upper or lower 32

bits). The Execute stage determines the unit to which the instruction

should be sent (the B-arithmetic unit, the Secondary Operand Unit

(SEOP) or PROP itself in the case of Organisational orders) and

increments the Control Register (program counter) once the instruction

has been sent via the Central Highway to B or SEOP or has been

completed by PROP.

The PROP entity models the clocking system used to progress

instructions through the pipeline. As in the real PROP, instructions

are moved through the pipeline in a series of beats, with each

beat being generated when an instruction leaves PROP or is completed

by PROP itself (including the (non-)execution of instructions marked

Invalid (I)). Each beat propagates through the pipeline from the

Execute stage back to the Decode stage, and thence to the IBU, with a

1-unit HASE time delay between stages, representing the 10 ns stagger

between stages in the real PROP (this stagger was necessary because of

the nature of the ECL technology used to implement MU5). Although the

timing between PROP stages is fixed, the actual generation of beats is

asynchronous in the model, as it was in MU5; there is no central

clock.

The function registers in the real MU5 had extra function bits

associated with them, one of which indicated whether or not the

instruction was valid. Other bits indicated a variety of different

conditions. These bits are represented in the HASE model by an

additional (character) Type field. This Type field is used to

represent the various types of instruction and address packets used

throughout the model, as shown in Table 1.

| A | ACC instruction with named variable finding NEQ in PROP NS |

| B | first phase of a Double ACC instruction finding NEQ in PROP NS |

| C | Compare result |

| D | first phase of a Double instruction |

| F | "From address" for branch prediction |

| I | Invalid instruction |

| K | acKnowledge packet, e.g. B to Highway to PROP |

| L | Load phase of a string-string order |

| M | Modifier request to B-Arithmetic Unit |

| N | PROP Name Store NEQ request |

| O | Ordinary instruction request |

| P | Priority instruction request (as a result of a branch) |

| R | Read packet to memory |

| S | Sequence bit - first instruction of a predicted sequence

Store phase of a byte/string order in SEOP

SAC = source of NEQ data in PROP Name Store

|

| T | "To address", = new CO value, may be used for branch prediction |

| U | version of V used in PROP Assemble stage to select an operand read from OBS Name Store |

| V | Valid instruction |

| W | Write packet (from B or Acc or to memory) |

| Z | STOP packet from ACC to PROP |

Table 1 Packet Types

The influence of these Types on the various actions that occur in

the processor as different instructions are executed is explained

below with reference to the execution of the demonstration programs

pre-loaded into the model.

The Instruction Buffer Unit

The Instruction Buffer Unit (IBU) is implemented in the model as two

entities corresponding to the two main sections of the IBU in the real

MU5, the Store Request System (SRS) and Data Flow. As in the

real MU5, the SRS contains a Jump Trace, an associatively addressed

store that keeps track of the jump-from and jump-to

addresses of branch instructions.

The first action that occurs at the start of a simulation is that PROP

sends the address in CO (the program counter, always called the

Control Register in Manchester computers) to the Store Request

System. This address is loaded into the Advance Control register (AC)

and forwarded to the Store Access Control Unit (SAC), marked as a

Priority (P) request. The SRS then increments AC twice (instructions

are fetched in pairs), each time testing the new address against the

Jump-From field of the Jump Trace, and sends a second request to SAC

marked as an Ordinary (O) request. The IBU maintains an Outstanding

request counter and continues to send Ordinary requests to SAC whilst

the number of outstanding requests is less than or equal to the number

of empty buffers in the instruction return path in the Data Flow

section (there are 8 32-bit buffers in the model). The Outstanding

counter is decremented whenever the second instruction of a pair is

sent to PROP, allowing further instructions to be pre-fetched.

If a new value in AC matches an entry in the jump-from field of the

Jump Trace, the address read out from the jump-to field is substituted

for the matching address and pre-fetching of instructions is restarted

from the jump-to address. Whenever the SRS sends a request to SAC,

information about the request is loaded into an Unpack Record in the

Data Flow section. This information is used by the Data Flow section

to unpack the two 32-bit instructions returned from SAC - depending on

the jump-from and jump-two addresses, either or both of these

instructions may be required. One of the fields in this entry is a

sequence bit. If the sequence bit is set for a branch instruction

being sent to PROP, its Type field is set to S. This indicates to PROP

that the instruction is being followed by instructions at the jump-to

address, rather than those in normal sequence. Simulation experiments

undertaken during the design of MU5 showed that this system, using 8

lines in the Jump Trace, would correctly predict around 75% of

branches.

The Data Flow section receives instructions in pairs from SAC, unpacks

them according to the entry in the appropriate entry in the Unpack

Record and enters them into the instruction buffers. These are

implemented in the model as a drop-down stack, i.e. an

instruction is taken off the bottom of the stack whenever PROP

requests one and each new instruction is entered into the lowest free

position in the stack.

The Secondary Operand Unit

The Secondary Operand Unit is mainly concerned with accessing data

structure elements (typically array elements) specified as secondary

operands by means of descriptors. It consists of three major sections,

the Descriptor Addressing Unit (Dr), the Operand Buffer System (OBS)

and the Descriptor Operand Processing Unit (Dop). An instruction that

specifies an array element picks up its descriptor from the Name Store

as it passes through PROP. PROP sends the instruction to Dr, where it

is loaded into the D (Descriptor) Register (DR). If the operand kind

field specifies a modified access, PROP also sends a command to the

B-Arith Unit telling it to send the value in the B register to Dr. If

the Base specified in the instruction is D (not a real base register),

the existing descriptor in DR is used.

Dr actually contains two descriptor registers, DR and XDR; XDR is used

by string processing orders, as described below in the String

Processing Program section. In the model, each 64-bit descriptor is

held as two successive 32-bit integers in memory, the most significant

word containing the Type, Size and Bound/Length fields and the least

significant word the Origin. In the Dr registers, the more significant

half is displayed in a more readable, disaggregated form. Thus DR_TSB

contains three fields, the descriptor Type, the operand Size and the

Bound (or length in the case of a Type 1 descriptor). The

demonstration Program 1 in the model involves two descriptors, both of

Type 1, Size 3 (i.e. 23 bits, = 1 byte, mandatory

with Type 1 descriptors) and a Length of 10. In memory these values

appear as 1476395018.

In the Scalar Product program (Program 2) in the model, the

descriptors are Type 0, Vector descriptors. The Dr Unit adds the

modifier to the Origin to form the address of the required element and

performs a bound check by subtracting the modifier from the Bound. In

the real MU5, hardware space constraints meant that the adder used to

form the address was also used as the subtractor. This was less than

ideal, so the model assumes that there is a separate subtractor. If

the Modifier exceeded the Bound in MU5, an interrupt was generated; in

the model, the simulation is stopped and a report displayed in the

Output pane.

The address created by Dr is sent to OBS, which, like the Name Store

in PROP, is invisible to the programmer and exists only to improve the

instruction execution rate. OBS makes the necessary store request and

sends the 64-bit word it receives from SAC to Dop, which contains

masking and shifting circuitry to select the array element from the

appropriate position in the word. It does this using the Dop Bits,

generated by Dr at the same time as the address, and carried through

OBS with the instruction. The Dop Bits identify the Most Significant

Byte Address (MSBA), the Most Significant bit Address (MSbA) and the

Least Significant Byte Address (LSBA). These bits allow any 1, 4, 8,

16 or 32-bit element, or the whole word, to be selected from the

64-bit word sent to Dop.

In the model, OBS is made up of three entities that correspond closely

to the sub-units of OBS in MU5 itself. These are the Input Process,

the Queue and the Output Process. The Input Process contains the

associatively accessed Virtual Address field of the operand buffers, 8

lines for named 64-bit variable words and 8 lines for 64-bit array

element words. (In MU5 itself there were 24 lines for 64-bit named

variable words and 8 addressable lines for 128-bit array element

words, though these were implemented in hardware as 16 lines x

64-bits.) If the address field of an incoming instruction finds a

match in one of these lines, the line number is encoded as a Tag and

carried through the OBS Queue with the instruction. If there is no

match, a new line is allocated and its Tag is carried through SAC, the

CPRs and the Local Store, so that when the store word arrives at the

OBS Output Process, the Output Process can write the value into the

appropriate line in the Value Field and can set the Full bit in that

line. When an instruction is at the Head of the Queue, its Tag is used

to access the appropriate line in the Value Field.

The Queue has space for up to 8 instructions and is controlled by two

counters, the Head and Tail counters. Initially both are set to zero.

When the first instruction arrives it is written into location 0 and

the Tail counter is incremented. Subsequent instructions are written

into successive locations, modulo 8, unless the Tail counter becomes

equal to the Head counter, in which case the Queue is full and the

Input Process is held up. The Output Process continually checks for a

Queue Ready signal, which is set when there is a valid instruction at

the Head of the Queue and for which the corresponding Full bit is

set. When the Queue Ready signal is true, the Output Process copies

the instruction from the Head of the Queue, reads its operand store

word from the OBS Value Field and sends both to Dop. It then sets the

Type field of that instruction in the Queue to Invalid.

The Local and Disc Stores

The Local Store is modelled as four blocks of 256 words with blocks 0

and 2 being arrays of pairs of integers, block 1 an array of

instructions and block 3 an array of 8-character strings. The Disc

Store is similarly modelled as nine blocks, with one instruction block

and two data blocks for each program plus a character block for

Program 3.

Demonstration Program 1

Program 1 demonstrates the way in which many of the MU5 instructions

were implemented by the MU5 hardware, particularly the way in which

the Name Store worked. Table 2 lists the instructions in the program,

showing their virtual addresses (CO value), their actions and the

results they produce. Below the table is a detailed explanation of

what happens in the model as each instruction is executed.

Variables used by B, Dr and PROP instructions are normally held in the

PROP Name Store, while variables used by ACC instructions are normally

held in the OBS Name Store. However, because Name Store lines hold

64-bit store words, a 32-bit variable used by a B instruction can

sometimes be part of the same 64-bit store word as an adjacent 32-bit

variable used by an ACC instruction, and because the Name Store

protocol is copy-back rather than write-through, variables can

sometimes be in the "wrong" Name store. To avoid

"sloshing", i.e. variables being transferred back and

forth between Name Stores, a variable is only moved between Name

Stores when it is the target of a write instruction. The program shows

what happens in the Name Stores:

- as the PROP and OBS Name Stores fill up

- when a line currently in use but unaltered is re-allocated

- when a line currently in use and altered is re-allocated

- when a read access has to wait for a write order to complete

- when two write orders occur in close succession

- when an ACC instruction reads a variable in the PROP Name Store

- when an ACC instruction writes to a variable in the PROP Name Store

- when a B instruction reads a variable in the OBS Name Store

- when a B instruction writes to a variable in the OBS Name Store

| CO | Instruction | Action | NS line | Result |

| 65536 | Org NB_LD lit Z 16 | NB = literal | | RNB = 16 |

| 65537 | Org SFNB_PL lit Z 22 | SF = NB + literal | | RSF = 38 |

| 65538 | B LD V32 NB 0 | B = [VA 8.0] | P0 | B = 528 |

| 65539 | B ADD V32 NB 1 | B = B + [VA 8.1] | P0 | B = 1057 |

| 65540 | B MUL V32 NB 2 | B = B * [VA 9.0] | P1 | B = 560210 |

| 65541 | B ST V32 NB 3 | B => [VA 9.1] | P1 | [VA 9.1] = 560210 |

| 65542 | B SUB V32 NB 4 | B = B - [VA 10.0] | P2 | B = 559678 |

| 65543 | B DIV V32 NB 6 | B = B (dummy order) | P3 | B = 559678 |

| 65544 | B XOR V32 NB 8 | B = B xor [VA 12.0] | P4 | B = 559142 |

| 65545 | B OR V32 NB 10 | B = B v [VA 13.0] | P5 | B = 559678 |

| 65546 | B SHL lit Z 3 | B = B < literal 3 | | B = 4477424 |

| 65547 | B AND V32 NB 12 | B = B & [VA 14.0] | P6 | B = 16 |

| 65548 | B RDIV V32 NB 18 | B = B (dummy order) | P7 | B = 16 |

| 65549 | B RSUB V32 NB 17 | B = [VA 16.1] - B | P0 | B = 529 |

| 65550 | B ST V32 NB 11 | B => [VA 13.1] | P5 | [VA 13.1] = 529 |

| 65551 | B LD V32 NB 10 | B = [VA 13.0] | P5 | B = 538 |

| 65552 | B ADD V32 NB 20 | B = B + [VA 18.0] | P1 | B = 1086 |

| 65553 | B ST V32 NB 13 | B => [VA 14.1] | P6 | [VA14.1] = 1086 |

| 65554 | B SLD V32 NB 9 | SF = SF + 2

B => [VA 20.1]

B = [VA 12.1] |

P2

P4 | RSF = 40

[VA 20] = 0,1086

B = 537 |

| 65555 | STS STACK V32 NB 11 | SF = SF + 2

[VA 21] = 0,[VA 14.1] |

P3 P5 | RSF = 42

[VA 21] = 0,529 |

| 65556 | Org NBSF_PL lit Z -2 | NB = SF + literal | | NB = 40 |

| 65557 | Org SFNB_PL lit Z 20 | SF = NB + literal | | SF = 60 |

| 65558 | ACC LD V32 NB 1 | ACC = [VA 20.1] | P2 | ACC = 1086 |

| 65559 | ACC ADD V32 NB 3 | ACC = ACC + [VA 21.1] | P3 | ACC = 1615 |

| 65560 | ACC MUL V32 NB 4 | ACC = ACC * [VA 22.0] | O0 | ACC = 897940 |

| 65561 | ACC ST V32 NB 0 | ACC => [VA 20.0] | P2 -> O1 | [VA 20] = 897940,1086 |

| 65562 | ACC SUB V32 NB 6 | ACC = ACC - [VA 23.0] | O2 | ACC = 897382 |

| 65563 | ACC DIV V32 NB 8 | ACC = ACC / [VA 24.0] | O3 | ACC = 1602 |

| 65564 | ACC XOR V32 NB 11 | ACC = ACC xor [VA 25.1] | O4 | ACC = 1137 |

| 65565 | ACC OR V32 NB 12 | ACC = ACC v [VA 26.0] | O5 | ACC = 1653 |

| 65566 | ACC SHL lit Z 2 | ACC = ACC < literal 2 | O5 | ACC = 6612 |

| 65567 | ACC AND V32 NB 15 | ACC = ACC & [VA27.1] | O6 | ACC = 20 |

| 65568 | ACC RDIV V32 NB 16 | ACC = [VA 28.0] / ACC | O7 | ACC = 28 |

| 65569 | ACC RSUB V32 NB 18 | ACC = [VA 29.0] - ACC | O0 | ACC = 542 |

| 65570 | ACC ST V32 NB 15 | ACC => [VA 27.1] | O6 | [VA27.1] = 542 |

| 65571 | ACC LD V32 NB 14 | ACC = [VA 27.0] | O6 | ACC = 566 |

| 65572 | ACC ADD V32 NB 20 | ACC = ACC + [VA 30.0] | O1 | ACC = 1138 |

| 65573 | ACC ST V32 NB 13 | ACC => [VA 26.1] | O5 | [VA 26.1] = 1138 |

| 65574 | ACC SLD V32 NB 9 | SF = SF + 2

ACC => [VA 31.1]

ACC = [VA 24.1] |

O2

O3 | RSF = 62

[VA 31] = 0,1138

ACC = 561 |

| 65575 | B LD stack Z 0 | B = [VA 31.1]

SF = SF - 2 | O2

- | B = 1138

SF = 60 |

| 65576 | B ST V32 NB 10 | B = [VA 25.0] | O4 -> P4 | [VA25.0] = 1138 |

| 65577 | Org NB_LD V32 Z 0 | NB = [VA 0.0] | P5 | RNB = 8 |

| 65578 | Org SFNB_PL lit Z 6 | SF = NB + literal | | RSF = 14 |

| 65579 | STS D_LD V64 NB 0 | D = [VA 4] | P6 | DR_TSB = 1 3 10

DR_O = 524288 |

| 65580 | STS XD_LD V64 NB 1 | XD = [VA 5] | P7 | XDR_TSB = 1 3 10

XDR_O = 524328 |

| 65581 | STS MOD lit Z 5 | DB = DB - literal

DO = DO + literal | | DR_B = 5

DR_O = 524293 |

| 65582 | STS XMOD lit Z 3 | XDB = XDB - literal

XDO = XDO + literal | | XDR_O = 7

XDR_O = 534331 |

| 65583 | STS D_ST V64 NB 2 | D => [VA 6] | P0 | [VA 6] = 1476395013

524293 |

| 65584 | STS XD_ST V64 NB 3 | XD => [VA 7] | P1 | [VA 7] = 1476395015

524331 |

| 65585 | STS D_SLD V64 NB 1 | SF = SF + 2

D => [VA 8]

D = [VA 5] | P2 | RSF = 16

[VA 8] = 1476395013

524293

DR_TSB = 1 3 10

DR_O = 524328 |

| 65586 | ACC STOP lit Z 0 | Stops simulation | | |

Table 2 Demonstration Program 1

Org NBld lit Z 16

NBld is an example of a base manipulation order, all of which are

executed in a similar fashion. Here the NBld instruction loads literal

value 16 into the Name Base register (RNB). Since a subsequent instruction

might well use the Name Base, the Decode stage sets a hold-up in the

PROP timing chain such that no more instructions are taken from the

IBU until the NBld instruction has completed. In principle, because

the operand is a literal in this case, the instruction could be

completed immediately but, because the operand could be of any kind,

the simplest solution is to hold up subsequent instruction regardless

of the kind of operand. The instruction proceeds through the pipeline

followed by copies of the instruction marked Invalid, until it reaches

the Execute stage. Here the operand is sent from the Highway Input

(HI) register to the Central Highway and thence back to the Highway

Output register (HO). Once it has been received in HO, the value is

sent to the Decode stage and loaded into RNB. (In the real MU5, the

name+base adder was used to execute base manipulation orders; the model

assumes for simplicity that there is an adder in the Decode stage.) At

the same time the Control register (CO) is incremented and the hold-up

is released.

Org SFNBpl lit Z 22

This non-overlapped base manipulation instruction adds the literal

operand 22 to the value in RNB and writes it into RSF, thus setting

the top-of-stack location to 38, above the named variables that are

about to be used for the B instructions.

B LD V32 NB 0

This instruction loads the B register with the value of the 32-bit

word held at the virtual address formed by adding 0 to the value in

RNB, i.e. address 16. Because Name Store lines hold 64-bit

words, this address is shown as 8.0 in Table 2, i.e. it is the

32-bit word held in the most significant half of 64-bit word 8. So

address 8 is presented to the virtual address field of the Name Store

in the Associate Stage of the PROP pipeline. The virtual address

field contains three subfields: the virtual address itself, a Valid

bit and an Altered bit. Initially the Valid and Altered bits are all

set to 0, so this first Name Store access does not find a match with

any of the entries because they are all invalid. This is detected when

the instruction reaches the Read stage where the content of the Line

Register (LR) is tested. LR contains one bit per line, each showing

the result of the match with that line. Only one line, or none, will

show a match for any one instruction, in this case none. This

constitutes a Name Store Non-Equivalence (NSNE) which is dealt with as

follows.

A hold-up is set (in the PROP entity) such that the Decode, Add,

Associate and Read stages of the pipeline enter the Held state until

the NSNE actions have been completed. The failing address is carried

through the PROP pipeline with the instruction marked as an N Type in

the model. When this instruction reaches the Execute stage it is sent

to the Descriptor Addressing Unit and thence to OBS. The OBS Name

Store is meant to store values being used as variables in Accumulator

instructions. However, names can sometimes be in the "wrong"

Name Store, e.g. because a 32-bit name being used in a B

instruction and a 32-bit name being used by an Accumulator instruction

can be in the same 64-bit store word, so a check must always be made

in the OBS Name Store. OBS sets a variable in PROP (not displayed in

the model) to indicate the source of the required store word (OBS or

the Store Access Control Unit (SAC)). Since this is a B instruction,

and since the OBS Name Store is empty at this point, the required

store word will come from SAC, so OBS sends the address to SAC, which

accesses the CPRs to translate the virtual address to a real address,

and this is sent to the Local Store.

Once PROP know that the required store word will come from SAC, it

selects a Name Store line to contain the required virtual address and

64-bit store word using the Line Pointer (LP) register. LP contains

one bit per line, with the first initially set to 1 and the rest to

0, i.e. it points to the first of the 8 lines (line 0). After

each NSNE the single bit in LP is shifted one place, modulo 8, to

select the line to be used at the next NSNE.

The value read from the Local Store is returned to SAC and thence to

PROP, which updates its Name Store Address Field and Value Field

(with values 528 and 529 in this case), releases the hold-up and

allows the instruction to proceed along the pipeline, marked as a V

Type. The Assemble stage selects the m.s. half of the 64-bit word

from the Value Field and when the instruction reaches the Execute

stage, it is sent to the Central Highway and thence to the

B-arithmetic Unit which loads the value (528) into the B register.

B ADD V32 NB 1

This instruction adds to the B register the value held at the virtual

address formed by adding 1 to the value in RNB, i.e. address 17

(8.1 in Table 2). This address does not cause an NSNE since the

virtual address of the corresponding 64-bit quantity (8) is already in

line 0 of the virtual address field of the Name Store. The value in

line 0 is simply read from the Value Field and the Assemble stage

selects the value in the l.s. half (529). The result in B is 1057.

B MUL V32 NB 2

This instruction multiplies the value in the B register by the value

held in the m.s. half of the word at the virtual address formed by

adding 2 to the value in RNB, i.e. address 18 (32-bit word 9.0

in Table 2). This address causes an NSNE that updates line 1 of the

Name Store with virtual address 9 and values 530 and 531. The result

in B is 560210.

B ST V32 NB 3

This instruction writes the value in B into the l.s. half of the word

at the virtual address formed by adding 3 to the value in RNB. It does

not cause an NSNE since the virtual address of the corresponding

64-bit quantity (9) is already in line 1 of the virtual address field

of the Name Store. However, the value to be stored is not available at

this point because the instruction still has to progress through the

pipeline to the B-Arithmetic unit. It would be possible simply to hold

up the pipeline in a similar manner to the hold-up used for base

manipulation orders but B store orders are more frequent, so a

different technique was used in MU5 and is replicated here. The

content of the Line Register is copied into a B Write register (BW).

BW also contains bits that indicate whether the value from B is being

written to a 64-bit operand (in which case zero is written to the

m.s. half) or (more likely) to a 32-bit operand and if the latter, to

which half of the Name Store word. The instruction proceeds through

the pipeline as for a non-store order. When it reaches the

B-Arithmetic Unit, and when all preceding instructions have completed,

the value is sent back to the Execute stage of PROP marked as Type

W. When the Execute stage completes its current action, it enters a

hold state while the new value is written into the Name Store line

addressed by BW. BW is then cleared and the Execute stage initiates the

next PROP beat. If a second B store order were to reach the Name

Store before the first had completed, or if a subsequent order were to

try to read the value which has not yet been written, a hold-up would

occur. This latter is the well known Read-After-Write situation.

B SUB V32 NB 4

This instruction subtracts from B the value held in the m.s. half of

the word at the virtual address formed by adding 4 to the value in

RNB, i.e. 32-bit address 20, 64-bit address 10.0. This address

causes an NSNE that fills line 2 of the Name Store with virtual

address 10 and values 532 and 533. The result in B is 559678.

B DIV V32 NB 6

There was no divider in the MU5 B-Arith unit because (a) there is

normally no need to use a divide operation when dealing with indices

and (b) divide needs a lot of hardware, so although this instruction

fetches an operand and sends it to the B-Arith unit, B remains

unaltered. The operand is at the virtual address formed by adding 6 to

the value in RNB, i.e. 32-bit address 22, 64-bit address

11.0. It also causes an NSNE that updates line 3 of the Name Store

with virtual address 11 and values 534 and 536. What actually happened

in MU5 is lost in the mists of time, though clearly no compiler would

ever have tried to invoke a B DIV or B RDIV.

B XOR V32 NB 8

This instruction forms the eXclusive OR of B with the value held in

the m.s. half of the word at the virtual address formed by adding 8 to

the value in RNB, i.e. address 12.0. It also causes an

NSNE that updates line 4 of the Name Store with virtual address 12 and

values 536 and 537. The result in B is 1536.

B OR V32 NB 10

This instruction forms the logical OR of B with the value held in the

m.s. half of the word at the virtual address formed by adding 10 to

the value in RNB, i.e. address 23.0. It also causes an NSNE

that updates line 5 of the Name Store with virtual address 13 and

values 538 and 539. The result in B is 1562.

B SHL lit Z 3

This instruction shifts the value in B three (binary) places to the left.

The result in B is 12496, i.e. 1562 * 2^8.

B AND V32 NB 12

This instruction forms the logical AND of B with the value held in the

m.s. half of the word at the virtual address formed by adding 12 to

the value in RNB, i.e. 32-bit address 28. It also causes an NSNE that

updates line 6 of the Name Store with virtual address 14 and values

540 and 541. The result in B is 16.

B RDIV V32 NB 18

As for DIV, the absence of a divider in the B-Arith unit means that B

remaisn unaltered. The operand is nevertheless fetched and sent to the

B-Arith unit from the virtual address formed by adding 17 to the value

in RNB, i.e. 32-bit address 34. This also causes an NSNE that

updates line 7 of the Name Store with virtual address 17 and values

546 and 547.

B RSUB V32 NB 17

This instruction subtracts B from the value held in the m.s. half of

the word at the virtual address formed by adding 17 to the value in

RNB, i.e. 32-bit address 33, 64-bit address 16.1. This also

causes an NSNE. All lines in the Name Store now contain valid entries

and LP points to line 0 again. The content of this line has remained

unaltered since the values were fetched from the Local Store, so it

can simply be overwritten with the new address and values (544, 545).

The result in B is 511.

B ST V32 NB 11

This instruction writes the value in B into the m.s. half of the word

at 64-bit address 13. This word is already in line 5 of the Name Store

so the instruction proceeds normally through the pipeline setting BW

to point to line 5 as it passes through the Read stage.

B LD V32 NB 10

This instruction requires the value in the l.s. half of the word at

virtual 32-bit address 26 and finds a match in line 5 of the Name

Store. However, BW is set to line 5 because of the previous

B ST order. This is an example of the classic

Read-After-Write situation. The B LD instruction is

held up in the Read stage of the pipeline until the value returned by

the B ST instruction has been written into line 5 of the Name

Store. The result in B is 538.

B ADD V32 NB 20

This instruction requires the value in 32-bit virtual address 36, which

causes an NSNE. The line selected for use (P1) currently contains 64-bit

address 9 which was modified by a previous B Store instruction. This

address and the corresponding values are therefore read out of the

Name Store and sent via SAC to the Local Store before the line is

updated with the new values fetched from the Local Store.

B ST V32 NB 13

This instruction sets the BW register to point to line P6 as it passes

through the Read stage and eventually writes the content of B to

32-bit virtual address 14.1.

B SLD V32 NB 9

This is a double (two-phase) instruction that writes the content of B

to the top-of-stack location, increments RSF and loads B with the

value held in 32-bit virtual address 18. The Decode stage creates a

hold-up in the PROP pipeline control logic and forwards the first

phase of the instruction to the Add stage, with RSF as the base and a

name value of 2, with the function field changed to ST and marked as

Type D. Once the Add stage has performed the name+base addition, it

writes the value of RSF+2 (40) to RSF. When the first phase reaches

the Read stage LR is zero, i.e. a Name Store non-equivalence

occurs. However, because the preceding instruction was also a write

order and set the appropriate digit in BW, this first phase is held up

(with BW2 displayed) until the write order completes. As soon as the

BW hold-up is released, the NSNE hold-up is invoked. The line selected

(P2) is in use but unaltered, so can simply be overwritten.

Once the NSNE actions are complete, BW is set to point to this line

and the instruction proceeds to the B-Arithmetic unit, without

incrementing CO. It returns the value of B to PROP and Name Store line

2 is overwritten with 0,1086 (stacked operands are all 64-bit). The

values returned from the Local Store as a result of the NSNE are thus

not used, but the NSNE actions have to be completed in order to ensure

that when the operand at this virtual address is eventually written

back the Local Store, it will not cause a page fault (as it could in

the real MU5, though not in this model). The second phase proceeds

through the pipeline as if it were a normal LD order. It finds 64-bit

virtual address 12 in line 4 of the Name Store and loads B with

537.

The second phase of the instruction increments CO and also copies the

new value of SF, carried through the pipeline in registers S3, S4 and

S5, into S6 and sets S6 valid (S6 has two components, its value and a

valid bit). If a branch occurs whilst a stacking instruction is in the

pipeline, the value in SF will be incorrect and must be replaced by

the value in S6. An organisational order that alters SF sets S6

invalid.

STS STACK V32 NB 11

The STACK instruction was designed to allow parameters to be passed

from the name space of a calling procedure to the name space of a

procedure being called. As in the case of the SLD instruction, STACK

is a two-phase instruction. In this case, the first (Type D) phase

accesses the operand at 32-bit virtual address 16+11 (26.1), currently

in line 5 of the Name Store (with value 511). Because there is an

outstanding B write, however, the STACK order must wait for this write

to complete before it can proceed beyond the Read stage. Once the BW2

hold-up is reset, the order proceeds and 511 is sent to the Central

Highway by the Execute stage and returned to HO.

The second phase increments RSF by 2 to create a new top-of-stack

address (64-bit address 21). The resulting NSNE generates an access to

the Local Store and the values (554/555) are loaded into line 3 of the

Name Store. The 64-bit value field is then overwritten, with zero in

the m.s. half and the 32-bit value being stacked in the l.s. half, the

result being that the line contains 0,511.

Org NBSFpl lit Z -2

The previous two instructions stacked two variables and left the Stack

Front register (RSF) pointing to the second of these. This instruction

adjusts the Name Base register so that it points to the first of the

two stacked values.

Org SFNBpl lit Z 20

This non-overlapped base manipulation instruction adds the literal

operand 22 to the value in RNB and writes it into RSF, thus setting

the top-of-stack location to 60, above the named variables that are

about to be used for the ACC instructions. It sets S6 invalid.

ACC LD V32 NB 1

The operand for this instruction is the l.s. half of the 64-bit

operand stacked by the B SLD instruction. Because this is an ACC

order, this operand is in the "wrong" Name Store but it

remains here and its value is carried through Dr, OBS and Dop as a

literal. Its value (1086) is loaded into the Accumulator (ACC).

ACC ADD V32 NB 3

The operand for this instruction is the l.s. half of the 64-bit operand

stacked by the STACK instruction. This value is also carried

through Dr, OBS and Dop as a literal. The result in ACC is 1615.

ACC MUL V32 NB 4

The operand address for this instruction (64-bit address 22) does not

find a match in the PROP Name Store but this does not cause an NSNE.

Instead, the instruction Type field is changed from V to A, so that

when the instruction reaches OBS, the OBS Input Process looks for a

match in the Name Store section of the Operand Buffers. Since there

are no entries at this point, an OBS non-equivalence (OBSNE) occurs

and OBS takes similar actions to those in the PROP Name store,

i.e. the OBS Line Pointer (OLP) is used to select a line (O0)

in the OBS Name Store (i.e. the lower half of the OBS Buffers)

and a request is sent to SAC. The OBS Line Register (OLR) is encoded

as a tag and is carried through SAC and the Local Store and with the

OBS Queue entry for the instruction. When the store request is

returned to OBS the tag is used to select the appropriate line in the

Value Field for updating and when the instruction reaches the front of

the Queue the tag is used to read this same line. The resulting value

in ACC is 897940.

ACC ST V32 NB 0

The operand to be written to by this instruction is in the PROP Name

Store but because this is an ACC store order, the operand has to be in

the OBS Name Store. Being part of the variable stacked by the earlier

B SLD instruction, it is in the Altered state and must therefore

be written back to the Local Store before it can be deleted from the

PROP Name Store. An Acc Write Equivalence (AWE) hold-up occurs while

this request is being sent and then the instruction proceeds through

the pipeline in an A Type packet. When it reaches OBS, it causes an

OBSNE that creates an entry in line O1 of the OBS Name Store. As in

the case of a B ST order in the PROP pipeline, an ACC ST

order is not held up at this stage. Instead, a copy of OLR is stored

in register AW. When the instruction reaches Dop, the store word is

copied into register WR and the order proceeds to the Accumulator

Unit. When the preceding order has completed in the Accumulator Unit,

the result is sent to Dop via the Central Highway. Dop copies this

result into the appropriate part of WR and returns the content of WR

to OBS, where the Output Process updates the line in its Name Store

addressed by AW. (There was not space in the hardware of the real MU5

to include register WR; instead the value was re-read from the OBS

Names Store, updated in Dop and returned to OBS.)

ACC SUB V32 NB 6

ACC DIV V32 NB 8

ACC XOR V32 NB 11

ACC OR V32 NB 12

ACC SHL lit Z 0

ACC AND V32 NB 15

ACC RDIV V32 NB 16

These instructions are executed in the Accumulator Unit in an

analogous manner to the corresponding B-Arith instructions,

except that they cause lines in the OBS Name Store to be filled.

ACC RSUB V32 NB 18

This instruction requires the value in virtual address 29.0, which

causes an OBS NSNE. The line selected for use (O0) currently contains

64-bit address 22, whose corresponding values have not been targets of

a store order so remain unaltered and can simply be overwritten.

ACC ST V32 NB 15

This instruction writes the value in ACC into the m.s. half of the

word at 64-bit virtual address 27, currently in line 6 of the OBS

Name Store so the instruction proceeds normally through the pipeline

setting AW to point to line 6 as it passes through the OBS Input

Process.

ACC LD V32 NB 14

This instruction requires the value in the l.s. half of the word at

virtual 32-bit address 54 and finds a match in line 6 of the OBS Name

Store. However, AW is set to line 6 because of the previous ACC ST

order. This is another example of the classic Read-After-Write

situation. The ACC LD instruction is held up in the OBS Input Process

until the value returned by the ACC ST instruction has been written

into line 6 of the OBS Name Store. The result in ACC is 566.

ACC ADD V32 NB 20

The 32-bit virtual address for this instruction (60) causes an NSNE.

The line selected for use (O1) currently contains 64-bit address 20

and a value modified by a previous ACC Store instruction. This address

and the corresponding values are therefore read out of the OBS Name

Store and sent via SAC to the Local Store. At the same time, the Full

bit in the Value Field is reset to 0, so that when the instruction

reaches the output end of the Queue, it will be held up unless the

line has already been updated with the new values fetched from the

Local Store.

ACC ST V32 NB 13

This instruction sets the AW register to point to line O5 as it passes

through the OBS Input Process and eventually writes the content of ACC

to 32-bit virtual address 26.1.

ACC SLD V32 NB 9

Similarly to the B SLD instruction, this is a double (two-phase)

instruction that writes the content of ACC to the top-of-stack

location, increments RSF and loads B with the value held in 32-bit

virtual address 49. The Decode stage creates a hold-up in the PROP

pipeline control logic and forwards the first phase of the instruction

to the Add stage, with RSF as the base and a name value of 2, with the

function field changed to ST and marked as Type D. Once the Add stage

has performed the name+base addition, it writes the value of RSF+2

(40) to RSF. When the first phase reaches the OBS Input Process, it is

held up as a second ACC write instruction (with AW2 displayed), since

AW is set for the preceding ACC ST instruction. Once the ACC ST order

completes its write, an NSNE occurs. The new line selected (O2) is in

use but unaltered, so can simply be overwritten. Once the NSNE

actions are complete, AW is set to point to this line and the

instruction proceeds to the Accumulator unit. It returns the value of

ACC to OBS and line O2 is overwritten with 0,1138 (stacked operands

are all 64-bit). As in the case of the B SLD instruction, the values

returned from the Local Store as a result of the NSNE are not actually

used.

The second phase proceeds through the pipeline as if it were a normal

LD order. It finds 64-bit virtual address 24 in line O3 and loads ACC

with 561.

B LD stack Z 0

The value at the current top-of-stack location is in OBS line O2, so

this instruction causes an NSNE in the PROP Name Store. When the

N-Type packet reaches OBS, OBS finds that it has a copy in its Name

store and signals to PROP that it (OBS) will supply the store word.

Because this is a non-store order, however, the entry in the OBS Name

Store remains unaltered and PROP does not create an entry in its own

Name Store. The store word from OBS is copied into the VU register,

so a special packet Type (X) is used in the Assemble stage to

select VU rather than VF.

Instructions destined for the B-Arith Unit (or PROP or Dr) pass

through the Queue Bypass Line, rather than the Queue, allowing them to

overtake ACC instructions. This was done in MU5 for two reasons, one

concerned with the after-effects of a CPR NEQ (not implemented in this

model) and the other with performance. The B-Arith Unit, PROP and Dr,

situated earlier in the pipeline than the Accumulator Unit, are

concerned with suppling operand addresses to OBS in order to keep the

Accumulator Unit (which is executing the "useful" part of the program)

busy, so it would be counter-productive to queue instructions destined

for these units behind ACC instructions.

B ST V32 NB 10

The store word required by this instruction is also in the OBS Name

Store, so OBS supplies PROP with the store word, but because this is a

store order, OBS effectively deletes its entry (by resetting the Valid

bit in the Address Field and the Full bit in the Value Field) and PROP

creates one.

Org NB_LD V32 Z 0

This instruction is an example of the Name Base register being loaded

with a value accessed using the Zero base option, in this case in

virtual address 0. This causes a NSNE which requires the current contents

of line 5 of the PROP Name Store to be read out and sent to the Local

Store before the new address and value can be loaded.

Org SFNB_PL lit Z 6

The Stack Front register is set to point to an address above the name

space being used by instructions that follow it.

STS D_LD V64 NB 0

This instruction loads the pair of 32-bit variables held in 64-bit

virtual address location 4 into the two halves of the Descriptor

Register, DR_TSB, containing the Descriptor Type, Size and Bound/Length

(1-3-10 in this case), and DR_O, containing the Origin (524288 in this

case). The NSNE causes line 6 of the PROP Name Store to be read out

before the new address and values can be loaded.

STS XD_LD V64 NB 1

Similarly, the two halves of the XD Register are loaded with 1-3-10

and 524328. The Name Store line selected as a result of the NSNE can,

in this case, simply be overwritten.

STS MOD lit Z 5

STS XMOD lit Z 3

The MOD and XMOD orders operate on D and XD

respectively by adding the operand value to the Origin and subtracting

the operand value from the Bound/Length.

STS D_ST V64 NB 2

STS XD_ST V64 NB 3

These D_ST and XD_ST orders write the current values

in D and XD respectively to 64-bit virtual address locations 6 and 7

in Name Store lines 0 and 1 respectively. The contents of D/XD are

sent to OBS via the Bypass Register, then to Dop and from there to the

Central Highway and onwards to PROP. PROP is held up at the Name Store

Read stage until the value has returned and been written into the Name

Store.

STS D_SLD V64 NB 1

The D SLD order is split into two phases at the PROP Decode

stage, similarly to a B SLD or ACC SLD order. The

first phase proceeds as for the D ST order, i.e. it is

held up at the Name Store Read stage until the value in D has been

returned to PROP and written into the Name Store. The second phase

loads D with the descriptor previously loaded into XD.

ACC STOP lit Z 0

The STOP instruction is a feature of the HASE simulation model, not

MU5 itself. It stops the simulation once it has reached the

Accumulator Unit and sent a reply back to PROP; at this point all

other instructions in the pipeline have been completed. As it passes

through the processor, STOP causes the contents of those Name Store

words and OBS buffers that have been updated to be written back to

Local Store.

Scalar Product Program (Program 2)

The scalar (or dot) product program (Program 2) forms the sum

of the products of corresponding pairs of elements of two 10-element

vectors X and Y as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Scalar Product example

Table 3 lists the program instructions, showing their virtual

addresses (CO values) and their actions. The explanation below the

table of what happens in the model as the program is executed

assumes familiarity with the explanations given above of the actions

of the instructions in Program 1.

| CO | Instruction | Action |

| 65536 | Org NBld V32 Z 0 | NB = [VA 0] |

| 65537 | Org SFNBpl lit Z 6 | SF = NB + 6 |

| 65538 | B LD lit Z 0 | B = 0 |

| 65539 | ACC LD lit Z 0 | ACC = 0 |

| 65540 | ACC SLD SB NB 0 | SF = SF + 2

ACC => [VA 4]

DR = [VA 0]

ACC = [DR.origin + B] |

| 65541 | ACC MUL SB NB 1 | DR = [VA 1]

ACC = ACC * [DR.origin + B] |

| 65542 | B CINC lit Z 9 | Set T1 & T2 according to

B - 9

B = B + 1 |

| 65543 | ACC ADD stack Z 0 | ACC = ACC + [VA 4]

SF = SF - 2 |

| 65544 | Org BRne lit Z -4 | If T1 /= 0, CO = CO - 4 |

| 65545 | ACC ST V32 NB 4 | ACC => [VA 2.0] |

| 65546 | ACC STOP lit Z 0 | Stops simulation |

Table 3 Scalar Product Program

The first two instructions set up the base registers NB and SF. The

first (Org NBld V32 Z 0) loads RNB with name 0 (= 16). This

is an example of how, in compiled code in MU5, Name Base values for

each of the procedures in a program were held in the name segment

starting at location 0, and accessed using Base 0. The second

instruction (Org SFNBpl lit Z 6) adds the literal operand 6

to the value in NB and writes it into SF, thus setting the

top-of-stack location to 22, above the named variables that are about

to be used for the ACC instructions. It sets S6 invalid. The next two

instructions (B LD lit Z 0 and ACC LD lit Z 0)

initialises B and ACC to 0. B holds the index and loop count variable

(i) and ACC the running total of the scalar product.

The first instruction of the scalar product loop (ACC SLD SB NB

0) increments SF and writes the current content of the

Accumulator to the top-of-stack location. It then loads DR with the

descriptor of the X vector (0-5-10, 524288), instructs the B-Arith unit to send

the value in B to DR, forms the address of the ith

element of X and loads ACC with the corresponding value. The first

time this instruction is executed, it causes a Vector Store

non-equivalence in OBS, which writes the failing address into the

Address Field and sends a request to SAC. When the store word arrives

back from SAC it is written into the OBS Value Field and the Full bit

is set for that line. During the second iteration of the loop, the

address of the second element does not cause a non-equivalence because

the store word received as a result of the first non-equivalence

contains the first and second elements of the vector.

Likewise, a non-equivalence occurs during the third iteration but not

in the fourth, and so on. During the ninth iteration, the Vector Store

is full, so the first entry is overwritten. At the same time as

writing in the new address in this cycle, the Full bit is reset for

this line in the Value Field, so that if the instruction emerges from

the Queue before the store word is returned (as it does in this case),

the instruction does not pick up the previous value.

The multiply instruction (ACC MUL SB NB 1) multiplies the

element of vector X, loaded into ACC by the preceding instruction, by

the corresponding element of the second vector (Y). Similar to the

execution of the second phase of the SLD instruction, this instruction

loads DR with the descriptor of Vector Y (0-5-10, 524328, and forms

the required address by adding the modifier from B to the Origin

address. Likewise a non-equivalence occurs in the OBS Vector Store in

odd numbered iterations of the loop but not in even numbered

iterations.

The Compare & INCrement instruction (B CINC lit Z 9) is

executed as a two-part instruction in the B-Arith Unit. The first part

subtracts the incoming operand (9 in this case) from B, and sets the

test bits T1 and T2 accordingly, but without altering the value in

B. The second part increments B by 1. The B CINC comes before

the ACC ADD stack Z 0 instruction that adds the running total

of products back into the Accumulator because the branch instruction

that closes the loop (Org BRne lit Z -4) has to wait for the

comparison result to be returned to PROP before it can be executed,

i.e. the code has been re-ordered to optimize performance.

The first 10 times that the Branch-if-not-equal instruction (Org

BRne lit Z -4) is executed, T1 is set to /= 0 so the Branch is

taken. The first time this happens, the pipeline is cleared and the

jump-from Control address (65544) and the jump-to Control address

(65540) are both sent to the IBU to set up an entry in the Jump

Trace. Prefetching is restarted from 65539 but when the AC register

next gets to 65544, there is a match in the Jump Trace, so instead of

fetching the next instruction from address 65545, the ACC SLD

instruction and its successors are prefetched instead. When this

happens, the BRne instruction is passed to PROP marked as Type S. When

it reaches the Execution stage, and the Branch is taken again, the

pipeline is not cleared, since this time the predicted

(out-of-sequence) instructions are already in the pipeline. On the

10th execution of the BRne instruction, however, the Branch is not

taken, so once again the pipeline is cleared and prefetching is

restarted at Control address 65545.

On leaving the loop, the result of the scalar product operation is

written to name 4 by the ACC ST V32 NB 4 instruction.

String Processing Program (Program 3)

The string processing program (Program 3) performs three tasks. The

first creates the composite string "Hello world" from

individual strings containing its component parts. The second finds

the first non-zero digit in the digit string 00083576 and places the

ASCII representation of its value in the B register. The third

searches for the word light in the sentence 'Let there be

light.'. Once it has been found, the B register indicates its

position in the sentence.

The strings are held in Block 3 of the Local Store. Each word in this

block contains 8 characters. Because the simulation code is written in

Hase++ (a superset of C++), it is strongly type-checked. Thus in order

to process these characters using the same simulated hardware as that

used for integer values, characters are converted to their ASCII

integer values and packed into a pair of 32-bit integer words whenever

they are read out of memory and, correspondingly, returning integer

words are unpacked during a write-to-store operation. Similarly in the

Descriptor Operand Processing Unit (Dop), each character is

manipulated as an integer value, so for visualisation purposes, an

extra register FRc is used to show the integer values in register FR,

converted to character format. The SSA_SSB register shown in the

Project Inspector frame is also a character display register,

corresponding to the actual register ssa_ssb used internally within

the code.

There are two types of string processing instruction: byte-string

and string-string. Executing each of them involves the execution of a

number of cycles of different types: first cycle, load

cycle, store cycle and compare cycle. Each

instruction starts with a first cycle which transfers the

operand specified by the instruction to the MASK_BYTE register in

Dop. The MASK is used in the BLGC and SLGC (logic) instructions (not

yet implemented in this model). BYTE is used as the source byte in a

byte-string instruction and as a filler byte in some string-string

instructions. A load cycle fetches a byte from the source